01/2020 food & beverages

In Copenhagen, chef Matt Orlando is providing beautiful proof that modern gastronomy can be sustainable—and he’s fostering a new language around the topic of food waste in the process.

A woodsy bowl of whipped zander roe, garden herbs, and toasted seeds. (Photo: Chris Tonnesen)

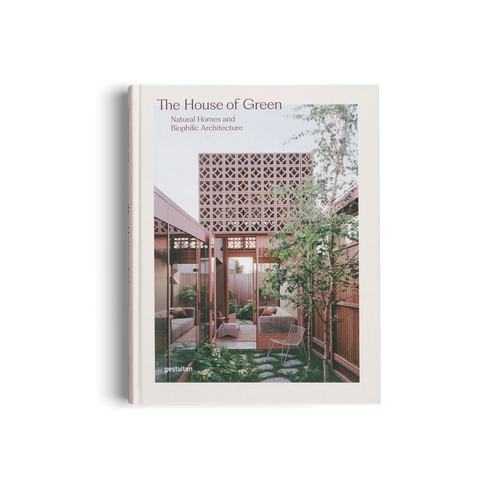

Matt Orlando is the chef and co-owner of Amass, a highly acclaimed Copenhagen restaurant known for its extremely progressive sustainability practices. Every single ingredient that comes into the Amass kitchen, whether it’s meat, fish, or vegetable, is used, whether in its original or upcycled form and what little can’t be used—or composted—is turned into biofuel. The restaurant’s recycling system is one of the epic proportions, as is its garden, which grows 80 kinds of plants. On the grounds of his second establishment, a brewery called Broaden & Build that he opened in 2019, Orlando opened a research facility dedicated to food waste. The chef’s commitment to sustainability does more than inform his restaurant’s practices, it also determines the way he puts food on his plates.

Growing up in San Diego, Orlando didn’t spend a lot of time thinking about the restaurant industry’s environmental impact, much less about fine-dining. “I wanted to be a professional snowboarder,” he says, and to that end, he eventually moved to Lake Tahoe, where he practiced the sport 150 days out of the year. He also discovered that “one percent of snowboarders make money.” Following that revelation, he decided to return to San Diego, where he had worked in restaurant kitchens since he was 14.

Amass was what he calls a “normal” restaurant, but six months in, the Amass winter closure gave the chef the opportunity to step back and consider what he wanted for the restaurant

He took a job working for Francis Passot, a French-born chef who changed Orlando’s perspective on cooking, ingredients, food, and life in general. “It was consuming, working for him because he was so passionate,” Orlando says. “You couldn’t help but be swept up in the wave of passion he had.”

Mackerel with green strawberry, lettuces, and rapeseed oil. (Photo: Amass)

Three years later, Orlando decided to move to New York to pursue his dream of working in fine dining. After stints at restaurants like Le Bernardin and Aureole, he got the opportunity to work in the United Kingdom at Belmond Le Manoir aux Quat'Saisons and the Fat Duck. It was at the latter that he met René Redzepi, who had come to eat there. Later, the two chefs began talking over beers, and Redzepi invited Orlando to work at Noma, which at the time was not the world-famous gastronomic mecca it is today. After working for Redzepi as his sous chef, Orlando returned to New York to spend three years as a sous-chef at Thomas Keller’s Per Se, then returned to Noma to take on the role of head chef. In 2013, he and his wife, Julie Bergstrom Orlando, whom he’d met while working at Noma, opened Amass in a former shipyard warehouse.

This focus on sustainability has transformed not only the restaurant’s practices but also the way food appears on its plates

Orlando opened Amass was what he calls a “normal” restaurant, but six months in, the Amass winter closure gave the chef the opportunity to step back and consider what he wanted for the restaurant. “A friend had asked me what was next, and the word ‘responsibility’ kept bouncing around in my head,” he recalls. “I didn’t know what it meant in the context of the restaurant, but it clicked right before we came back from vacation. I said to my wife, ‘This is what we’re doing to do; this is what we need to do.’” When he shared his plans with his staff, he said to them, “I don’t know how we’re going to do this because I’ve never worked in a restaurant like this, and you’ve never worked in a restaurant like this, but that’s okay because we’re going to figure it out together.”

A bowl of grilled white asparagus, chamomile, and lobster oil. (Photo: Chris Tonnesen)

It’s only been in the last year, Orlando admits, that he’s felt like he and his team have really started to figure out where they want to go: “It’s a direction where every single component of every ingredient we use is thought of as an ingredient and not as trash or waste,” he says. “We never use those words in the restaurant. It’s almost like you need to learn a new language to describe those products, because otherwise, no matter how delicious they are, they’re viewed as less than their original form.” This focus on sustainability has transformed not only the restaurant’s practices but also the way food appears on its plates. “I’ve definitely become way more vegetable-based in my cooking,” Orlando says.

“When I worked in New York, it was very protein-based: if you had a protein on a dish, then the vegetable should equal 30 to 40 percent of that protein. Now it’s the opposite.” The Scandinavian mindset towards plating has also had an impact. “You really want to respect the vegetable you’re putting on the plate,” Orlando says. “For me, it’s really important that you know you’re eating a piece of white asparagus. It hasn’t been puréed or gelled; it’s like you look at that plate and there’s no doubt in your mind. That’s also very Scandinavian. I think we all value produce here so much more because it’s such a short window of when the product is available; we want that product to be center stage.”

White asparagus topped with a vegetable purée of borage and fennel, which grow together in the Amass garden. (Photos: Chris Tonnesen)

One pet peeve he has about plating, he adds, is when food is spread out across the plate with a small dot of vinaigrette or sauce, “and the waiter says, ‘Okay, make sure you get a bit of everything when you get a bite.’” At Amass, he wants his guests to eat everything together—but he doesn’t want to have to instruct them, either. “So for us, when we plate, we take that into consideration—can they pick up a piece of asparagus and get everything in one bite?” The question that guides him, he says, is “how do we plate food that looks beautiful—and that people can eat however they want?

Learn how to turn a great dish into an artwork through Story on a Plate