02/2021 Escape

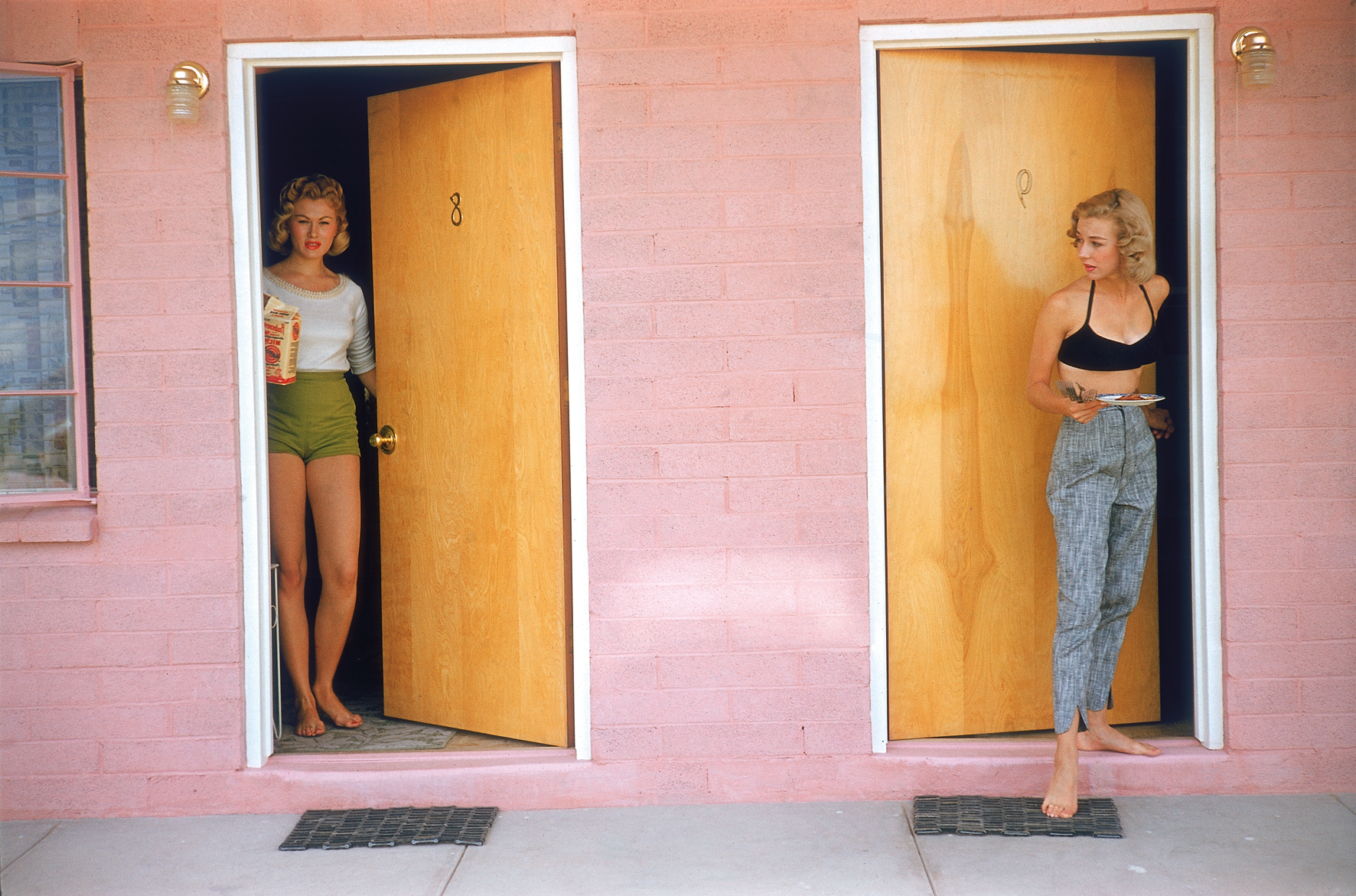

Cops can get testy when youths run through the famous favelas of the city at night. All the more reason for Júnior Negão and his crew to occupy the streets. “We are not a club, we are a crew, a cultural resistance,” announces Negão, who founded Ghetto Run Crew in Rio de Janeiro after a late-night run with his wife, Gisele Nascimento, in 2013. Today, many in the crew run after midnight. “Running at night was a way of engaging with other cultural activities that only really happened after dark, such as samba, skateboarding, and graffiti,” Negão explains. The crew suffered a lot of repression at first, principally because the police felt it was not acceptable to go running in the favelas at night. With persistence and determination, however, they have managed to create a movement.

Negão never imagined himself as a runner. “When you live at the top of mountains or hills, in the places where the favelas are, running is a normal part of life… but I decided to use it as a tool for social empowerment.” Favela residents are looked down upon by the rest of society and face a constant struggle to survive. Women have it particularly tough. “My mother, my wife, so many others, who despite being real-life winners, are still undervalued,” says Negão. “The idea with Ghetto Run was to bring these women together and, through running, provide them with the means to strengthen themselves as individuals.” Running became a gateway to confidence, the kind of confidence that transcends sport. “You can overcome any challenge in any area of your life,” explains Nascimento as she talks about what she’s learned from running. “Whether as a professional, as a mother, or as a daughter, I learn to be a better human being. And that does not depend on anyone else. It depends only on you.”

The Ghetto Run Crew originally targeted women as Ghetto Run Girls. The idea was to help young women achieve a sense of place and empowerment in society, through coming together to take over the streets and make others aware of their presence. (Photo: Ghetto Collective, On The Run)

Independence is the lifeblood of Brazil’s creative communities, but it is a freedom that many are concerned is under threat as President Jair Bolsonaro attempts to shape the country according to conservative values. On the day of his inauguration in January 2019, Bolsonaro dissolved Brazil’s Ministry of Culture, and it was later announced that public funding for the arts would be limited to government-sanctioned projects. As Nascimento explains: “We live in a society that plots to assassinate the culture, ancestry, and artistic creativity of the people. The Ghetto Run Crew has become what it is today without any government looking out for us, without providing us with documents, space to work, or investment. So we do it our way—down to earth, with planning, one step at a time.”

Negão calls this process “citizen solutions,” which often originate in the favelas and have produced some of Brazil’s most celebrated subcultures that are integral to the country’s creative capital. Negão grew up in a favela in Rio’s North Zone, where most Ghetto Run Crew meetups take place. He sees it as a privilege to represent the cultures that contribute to the city’s cultural economy. “It’s not just about us rising,” says Negão. “It’s about bringing our community, our society, with us on this journey. I never wanted to be a leader. I created the Ghetto Run Crew to help other movements tell a story.”

In 2019, police killed 1,810 people a year in Rio de Janeiro, an average of five per day. This highest number since official records began in 1998, but some argue the toll is much higher. Ghetto Run Crew are trying to reclaim the streets of the city in a positive way, both for people and police. (Photo: Ghetto Collective)

With 15 other storytellers in the Ghetto Run Crew and an extended family that runs into the hundreds (including rappers, skateboarders, graffiti artists, dancers, DJs, and poets), they have created a powerful space in which their stories can be told. “We are a counterculture because we allow other body types, other lifestyles, to participate in traditional running cultures,” says Negão. “We don’t use running as competition, but as a tool for cultural representation.”

Part of Negão’s mission is to increase Afro-Brazilians’ visibility in running, which he says isn’t immune from racism. “How many Black people have changed, are changing, and will change running? How many have built, are building, and will build strong bridges with their passion, and yet don’t have space in our memories? If the world’s best runner was white and called Rick Springfield instead of Eliud Kipchoge, you can guarantee the story would be different.” Ultimately, young people need to see that art, sport, and social engagement can earn them respect in the world. Creating such role models, and giving them a platform, is what Ghetto Run Crew is building toward. “The world has Jesse Owens, Tommie Smith, John Carlos, Aída dos Santos, Colin Kaepernick, Charlie Dark, and many others who prove the value of Black power,” Negão says. “One day, we will also be on that list.”

More than just a physical activity, running is about community and wellbeing. Find out more about On The Run.