05/2021 architecture & interior

Throughout much of civilization, architecture has been a medium that marries a residence with verdure and vegetation. One of the first and most notable examples of vertical gardens can be found in the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, which famously was more roof garden than green walls. In ancient Japan, techniques such as Shokusai (planting) were used to cover buildings with climbing plants and garden architecture. This fuse of nature with building surfaces was common across the world, from Scandinavian shelters to Latin American haciendas, later dubbed ‘green façades.’

In the 19th-century, the Garden City movement taking place in England became a thriving display of green façades. William Robinson and Gertrude Jekyll designed outdoor vegetated rock walls used for screening and boundaries in gardens. Then around the 1930s, climbing plants and green architecture started to experience a decline due to modern building techniques and attitudes. Monumental steel, concrete, and glass structures became the cultural norm for decades, but today, green façades and architecture are undergoing somewhat of a renaissance. In a tribute to this resurgence, our latest release Evergreen Architecture is a journey into flourishing green oases and the positive impact they can have.

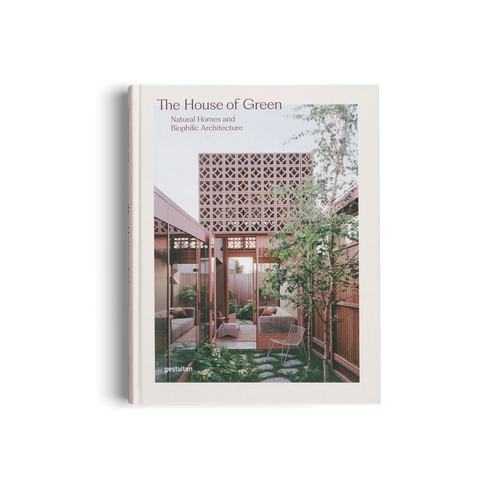

Representing a new urban habitat, Bosco Verticale (Vertical Forest) is a pioneering prototype for the future of green housing. Measuring 80 and 112 meters (262 and 367 feet) in height, the towers support almost 800 trees. (Photo: Stefano Boeri Architetti, Evergreen Architecture)

As climate change asks more from all of us, from the architect to the balcony retiree, vertical gardens are proving to be a valuable tool that can be both beneficial to humanity and nature. As an architectural movement, it strives to reduce the number of resources consumed in the construction and operation of buildings and curtailing the harm done to the environment through pollution, emissions, and waste of its components.

Vertical gardens, green walls, and forest façades are both marvels of beauty and a preservation of ecosystems. They consume air pollution and later release oxygen, they also create a space for habitats to be reintroduced into cities and the countryside. French botanist Patrick Blanc is an archetype of the vertical garden—his ability to reacquaint nature with the core of a city has been a blueprint for a whole new generation. Blanc's Le Mur Vegetal (Vertical Garden System) approach allows both plants and buildings to live in harmony with one another. Whether the 25-meter-high Parisian green wall of L'Oasis D'Aboukir (the Oasis of Aboukir) or the Musée du Quai Branly, his method has been studied and applied in several cities across the world.

Green living walls can provide a cooling potential on the building surface, it decreases the energy consumption by increasing building thermal performance, it decreases the urban heat island effect (which occurs when cities replace nature with dense industrial materials that absorb heat), increases the interior air quality, and decreases noise pollution. Architects today are reimagining both cities and urban design, they are transforming exteriors into habitats and an alternative to the mundane of high-rises.

Not just an iconic addition to the Brisbane skyline, Urban Forest by Koichi Takada Architects and Binyan Studios is a statement on the potential for greening cities worldwide. Set to be completed in 2024, the tower will include a solar farm, a gray water recycling system, and a water filtering system for the 1,000 trees and 20,000 native plants. (Photo: Courtesy of Koichi Takada Architects and Binyan Studios, Evergreen Architecture)

“Architecture has to be instrumental in the fight against climate change,” states Koichi Takada in Evergreen Architecture. He leads an Australia-based architecture studio and is also a vocal advocate for green design in cities, with much of his work deemed pioneering in the design community. He says: “Buildings are responsible for around 40% of greenhouse gas emissions in the world. As a first step, we need to stop negatively impacting the environment and depleting the planet’s resources. Secondly, we must look at ways of reversing the picture.”

Takada embarked on a mission with his vision of Urban Forest in Brisbane, Australia. The structure demonstrates green architecture’s potential to solve climate problems. This carbon-neutral high rise will host over 1,000 trees and 20,000 plants, sourced from 259 native Australian species, and once completed, will be the country’s greenest building. Takada describes the project as the “evolution of mass greening,” because of the holistic way it considers sustainability.

To design tenable green spaces, architects must move beyond aesthetics to consider their endeavors’ financial, practical, and environmental implications. Nor can it be a PR stunt to transform a building 'green' while ignoring fundamental questions such as: Can the plants survive and thrive? Will the roofs be able to sustain nature? Are the species sustainable and climatized to the environment? Will the plants reduce energy consumption? Will they do enough to cool buildings?

The Bosco Verticale was designed to feature staggered, overhanging balconies, accommodating large tubs of vegetation and allowing for the continued growth of the maturing trees. (Photo: Stefano Boeri Architetti, Evergreen Architecture)

In one of the most ambitious vertical garden projects of recent memory, Italian architect Stefano Boeri worked with a group of experts in 2014 for the groundbreaking Bosco Verticale in Milan. The project is a prototype for a series of towers, which Boeri describes as being “a new format of architectural biodiversity.” Consisting of two towers, together they are home to 800 trees, 15,000 perennials, and ground-covering plants, and 5,000 shrubs. Its “complex urban ecosystem” is equivalent to 30,000 square meters (322,900 square feet) of forest, condensed into a 3,000-square-meter (32,000-square-foot) footprint. Tended to by climbing arborists—nicknamed the ‘Flying Gardeners’—and watered using an advanced irrigation system, it is a spectacularly verdant anomaly that enriches Milan’s skyline.

The past decade has seen architecture studios and homeowners adopting this style of design that has been rising in demand. From Medellín to Melbourne, a new era of consciousness design that ushers in a deeper connection between nature and humanity. This book presents an approach to architecture and living that reimagines how we can better be at one with the planet—sustainably and stunningly. Vertical gardens and green architecture have been around for millennia, but this book explores why they have never been more crucial in our existence.

See more from this blooming movement through Evergreen Architecture.