Your Cart is Empty

Buy a book, plant a tree.

Photographer Mattia Balsamini gives us a glimpse behind normally closed office doors

For those with a curious disposition, there's something quite magical about stumbling across the reportage photography of Mattia Balsamini. Both mysterious and revealing, his outsider or fly on the wall perspective provides a fascinating account of work life we may not otherwise get to discover. Or in the case of Mattia, a time of his life he set out to rediscover.

Growing up in northeastern Italy, Mattia's childhood was spent enveloped in the cross-generational Balsamini family business of designing and installing air-conditioning units. Located in the small town of Sacile, business took place on the bottom floor of a building that also contained his grandparents’ residence. Even though Mattia wasn't exactly sure what his father did for a living, he sat in the office each day after school soaking up the atmosphere at the intersection of work and home-life.

"I moved and played between these two worlds almost seamlessly, being accustomed to think they were one. Eating an afternoon snack, talking with my grandma, then walking downstairs to play with tools at the workshop, among busy working people."

Between a grandmother's willingness to nurture and the chaotic but captivating workshop, an inquisitive child would struggle to find a more stimulating environment. It's not hard to see why Mattia eventually took to photography, a medium that requires an eye for detail, flexibility, and confidence to step into the unknown.

After moving to Los Angeles in 2008, he went on to assist David LaChapelle before graduating with a BA in Advertising Photography at Brooks Institute. At this point, it might have been quite easy for Mattia to follow a certain path but his vivid perspective on the world growing up became increasingly difficult to contain.

Now based back in his beloved Italy, his multi-faceted approach to photography combines still life pictures, studio portraits, and landscapes that often weave compelling stories about people and their places of work. But we're not talking about your average office or workshop.

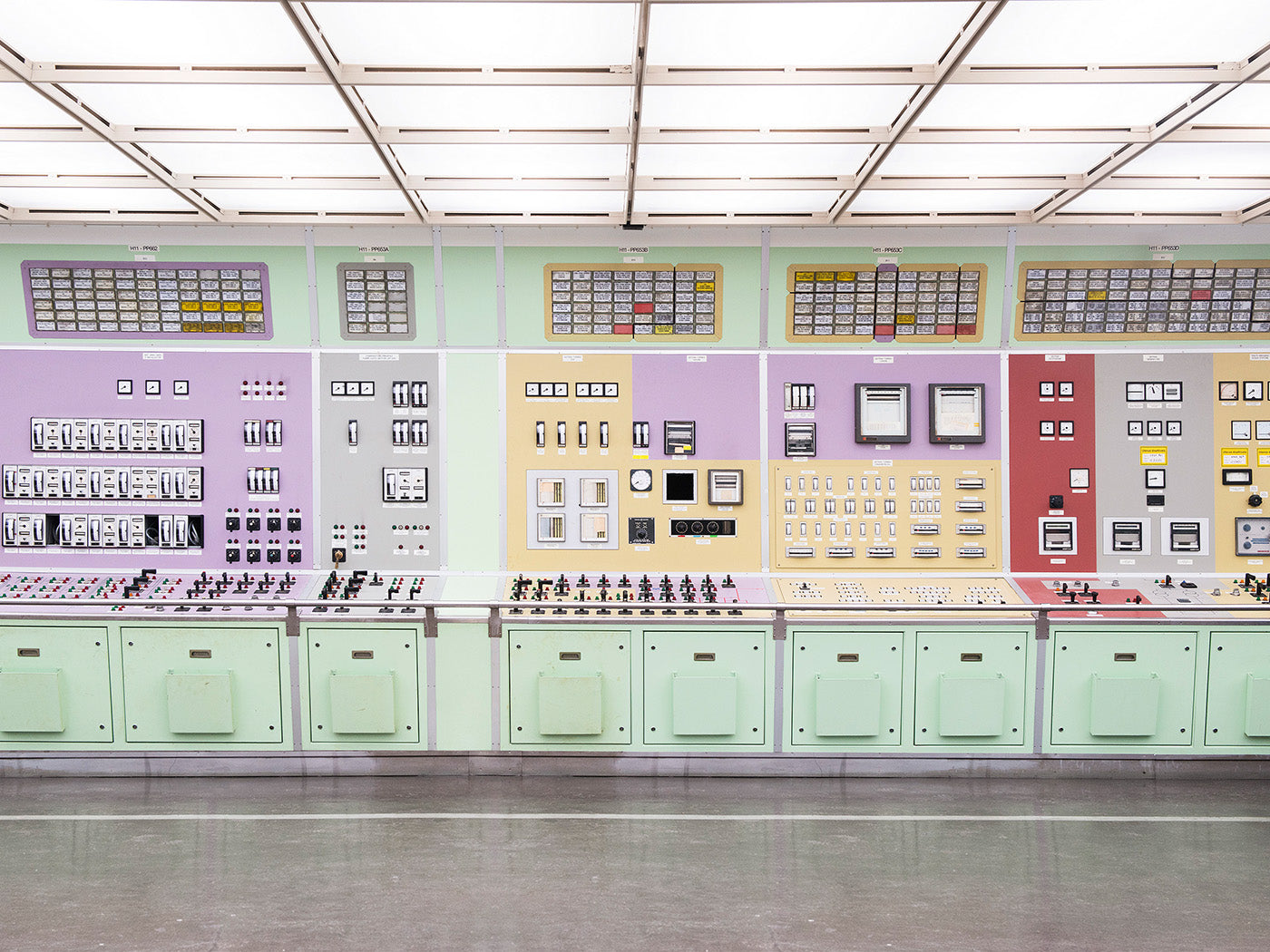

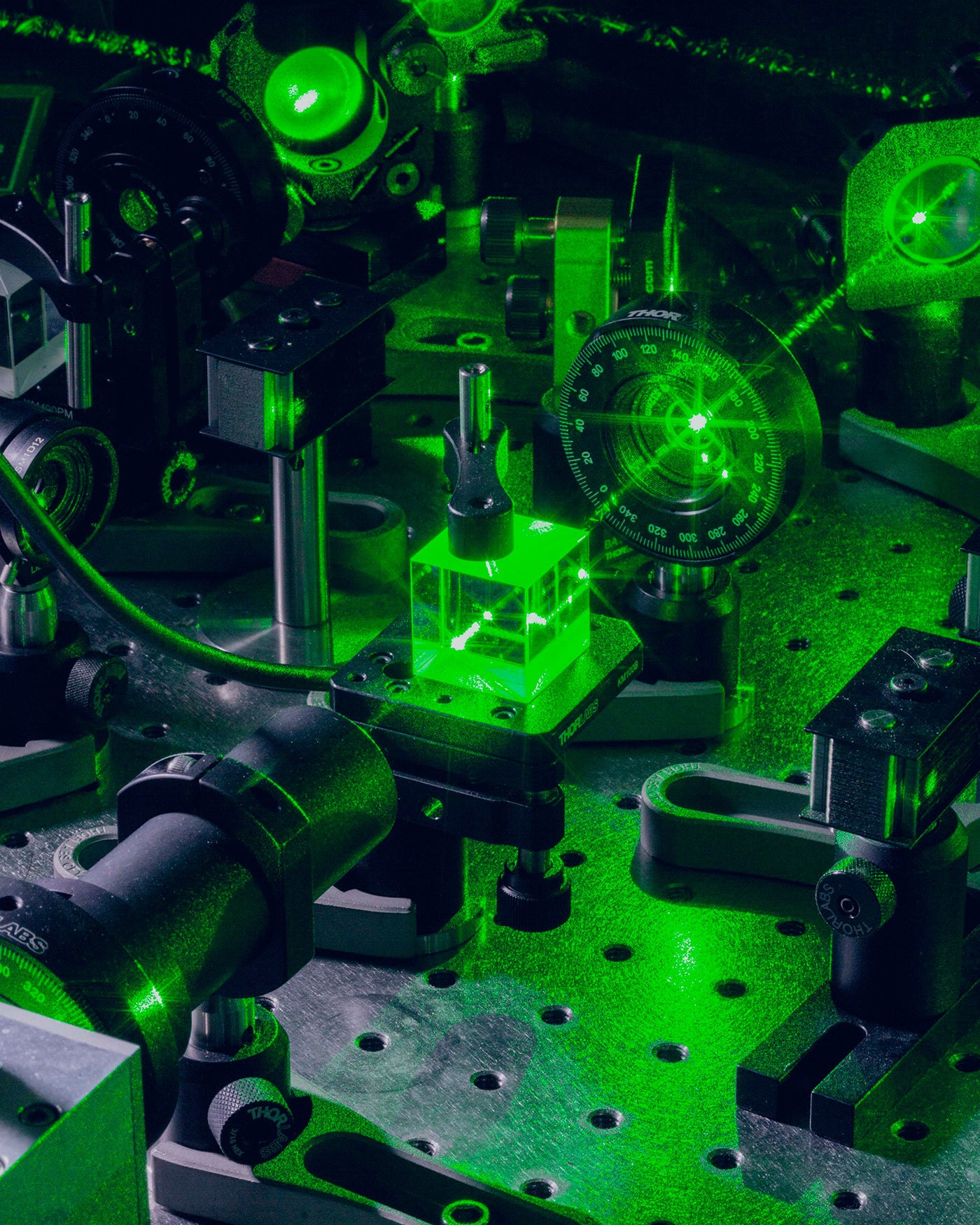

Recent editorials have seen him complete reportage projects in NASA, MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), the control room of a nuclear power plant, and in the automated robotic production lines of Electrolux. And it's the resulting images that attracted us to reach out to Mattia to find out more about his intriguing peek behind a normally closed curtain.

Many of your projects are related to subjects around industry and technology. How much of an influence has your childhood had on your work?

The fast shift of the post-war period that took place in my hometown (like in most of northeastern Italy), projected the area from rural poverty to riches in a few decades–riches that weren't created thanks to oil, gas or gold, but through the only available resources: time, space, and labor. What I started questioning in my photographic practice is how domestic and work settings, typical of this area, intersect with each other.

In the past six years, working on editorial assignments, alongside my personal work, I decided to partly demystify situations connected to the commercial work I was doing–many of them related to experiments, new technologies, industrial and highly automated processes. I used the photographic medium to break down what I was looking at, looking for simpler concepts, more easily associated with my childhood memories. I believe I became interested in re-discovering what I first saw when I was a kid.

The NASA project is fascinating. What was the most interesting thing you found out about the astronaut's preparation process?

The assignment was originally commissioned by GEO Magazin. Together with journalist Lars Abromeit, I followed the preparation of astronaut Alexander Gerst for Expedition 57 in three different countries, USA, Russia, and Germany. Two things struck me profoundly while working on this. The first one was being able to reach a new level of understanding of the technology involved in these missions. Seeing how many things can go wrong even just during long training session or simulation, and witnessing the immense amount of decisions these people and their support team have to take very quickly.

A lot of this technology has been around since the late sixties when mankind was only recently able to land on the moon. As an example, Soyuz is the name by which a series of vehicles were developed for the space program of the Soviet Union. The first manned flight took place on April 23, 1967, and ended with the death of pilot Vladimir Komarov. Since 2011, the year in which the Space Shuttle service ended, the Soyuz is the only spacecraft still capable of transporting astronauts to the International Space Station. This capsule, or its replica to be more precise, has been used for Gerst’s training for most of the time we spent in Russia.

Industrial factory automation is a controversial topic in terms of how technology has affected the job market. With apps such as Instagram already making photography more accessible to the masses, as well as retouching capabilities, filters etc., do you think more advanced technology is better or worse for photography?

I honestly don’t see any issue with technologic advancement in the photographic field. Allowing more people to actually take better, more precise and, hopefully, more useful images, is, in my opinion, a beautiful gift. Of course, this competes partly with the allure of being a photographer, but I keep reminding myself this media was born first and foremost as a recording tool, a way of remembering, or seeing better, and later on some of its nuances turned out to be artistically and aesthetically pleasing as well. If my grandma is able to take a digital picture (perhaps even a particularly good one) of a flower with her smartphone because she loves to look at it, this looks to me like a return to what the medium was originally born for. The only question left to address could be if it is “fair” for this task to be so simple. I haven’t made up my mind about this yet.

How do you envisage the future of photography?

Photography, as we know, is relatively young compared to other forms of communication and art. Yet in my opinion, it is structured enough that maybe we can behold its DNA, which I think is pretty romantic.

Among the many experimental routes explored so far, it looks to me that photographers, many photography viewers, and users are still in love with a classical result. Despite technology, which can be extremely advanced, what makers and users seem to respond to the most, is an aesthetically pleasing, relatable, recognizable and somewhat, “classical” output. Of course, this is speculation, yet I believe a big part of what photography has been, it will always be.

What is the robotic structure you photographed at MIT? Should we be worried?

The robot in that image is an early stage of Atlas–a humanoid robot developed mainly by Boston Dynamics, with the financing and supervision of the DARPA (Advanced Research Projects Agency) of the United States. This 1.8 meter (5,9 ft) robot was designed for search and rescue activities. This one doesn’t actually worry me, yet the SpotMini (also by Boston Dynamics) may be a more intimidating, simply for its four-legged appearance. Both robots are able to open doors, jump, and perform very complex tasks.

A very intriguing research paper regarding this is The Uncanny Valley, a theory by Japanese researcher Masahiro Mori. The research experimentally analyzes how the feeling of familiarity and pleasantness generated in a sample of people by anthropomorphic robots, increases as their resemblance to the human figure grows. It gets to a point where the extreme representative realism produces, at the contrary, a sharp drop in positive emotional reactions arousing unpleasant sensations such as repulsion and anxiety.

And finally, who are the photographers or filmmakers who’ve had the biggest impact on your career?

Some early masters of The New Objectivity such as Albert Renger-Patzsch and Hein Gorny. They perfectly blend formal research about the appearance of objects and tools – visually reflecting on the interaction between function and form.

View more of Mattia's work at mattiabalsamini.com