Your Cart is Empty

Buy a book, plant a tree.

Once a form of escapism, Dreamscapes writer Rosie Flanagan discusses how the digital world is liberating design

Dreams have long been a subject of artistic inquiry. Where does our subconscious go during sleep? What do our dreamscapes mean and can they ever be made into physical spaces?

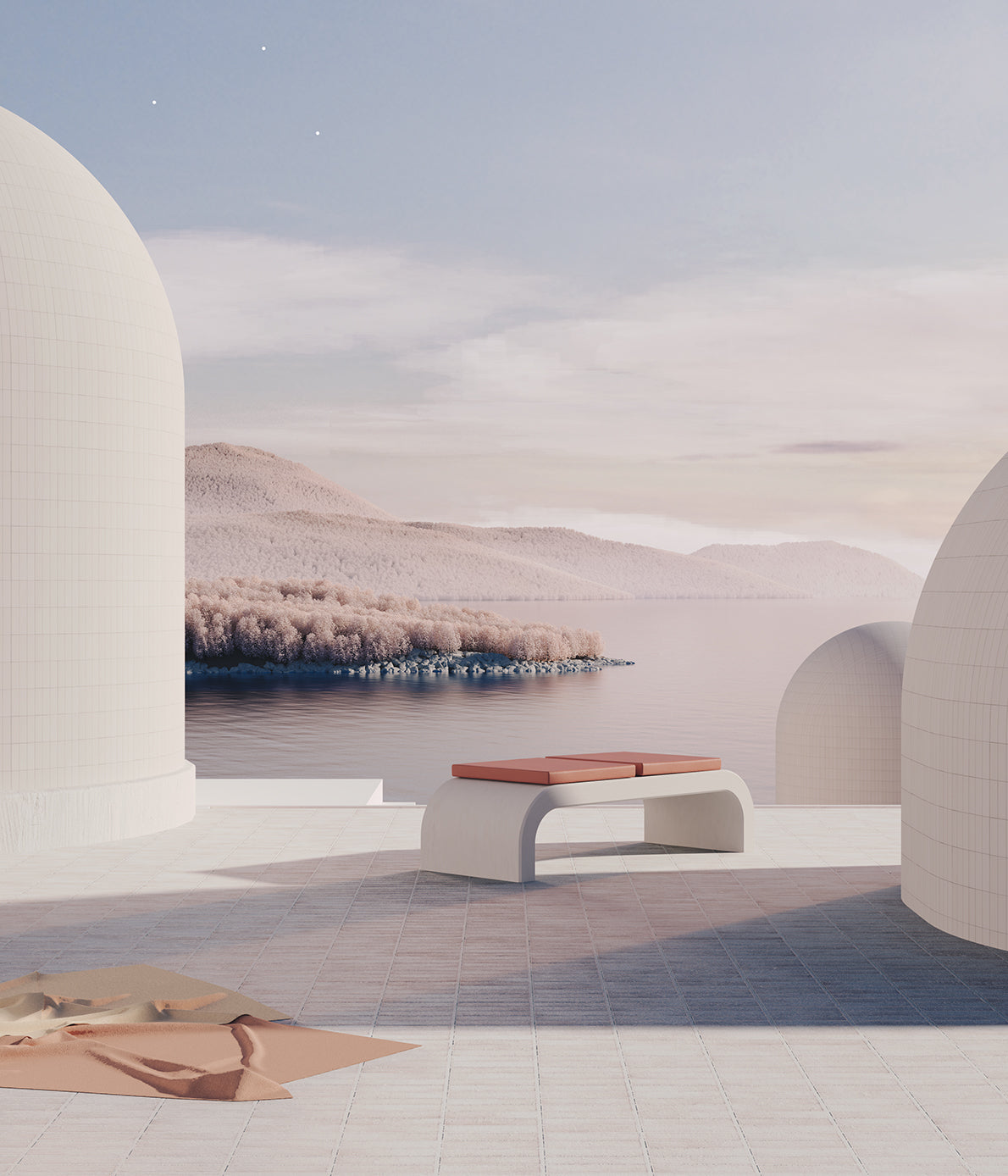

Where do we go when we dream? This surreal territory has proved fertile ground for a new generation of contemporary artists working at the intersection of architecture, interior design, and technology. Drawing upon utopian hopes and dystopian fears, the dreamscapes of these creations offer an intriguing insight into a new movement in digital art.

This rise is closely tied to the rise of technology and social media—a pairing that has had an immeasurable effect on creative mediums and, most notably, on the crossover between them. In the digital realm, art, interior design, and architecture are no longer distinct. In the dreamscapes featured in this book, they coalesce entirely.

The widespread use of 3D modeling programs has made this aesthetic intermingling possible. Architecture and design are no longer analog. Today, buildings can be realized digitally with software such as Rhinoceros 3D, Enscape, Lumion, and Octane. Renderings of houses have become common to the point of ubiquity, and it can often be difficult to distinguish between what is real and what is not.

Modeling software is not industry-specific; you don’t have to be an architect to design a building, or an interior designer to render a space. In recent years it has become increasingly popular among artists, who take the visual language of traditional CGI and apply it in new and interesting ways. In this book, this is exemplified by renders of impossible spaces that can not—and will not—be built.

Like many contemporary visual trends, the dreamscape movement has been shaped by the social media platform that it has proliferated on. On Instagram, user habits are regulated by the platform, and “likes” feed an algorithm that defines what is trending. In this digital echo chamber, trends spread memetically. The visual motifs common in dreamscapes—opalescent orbs, pink skies, curved doorways, swimming pools— recur across the platform in images of both art and life. While such elements and their popularity are not all new, these intriguing combinations are.

Within dreamscapes, different design movements mill alongside one another. Pastel postmodern structures are just as likely to house a surrealist pool and a suspended sphere as they are the undulating couches of Swiss artist Ubald Klug, or Faye Toogood’s recent but iconic Roly Poly Chair. As artists are employed to render advertising campaigns for everything from fashion to furniture and technology, such blurring of the real and unreal is increasingly common, and it’s an effective marketing tool.

Samsung’s “Perfect Reality” campaign from 2019 is an example of how rendering translates from art to advertising. In the two part video series advertising the QLED 8K television, the hyperreal nature of Six N. Five’s work conveys the ocular quality of the product. The campaign is set in a dreamscape where moons multiply and disappear, and “reality” is played to an audience through a television screen.

In 2018, the physical and the digital collided when artist Andrés Reisinger published a 3D image of the Hortensia Chair on Instagram. The dusky pink CGI lounge chair went viral, garnering thousands of likes and winning fans. Customers contacted the studio, asking to buy a piece of furniture that did not physically exist. Reisinger gave in to popular demand, and, in 2019, the Hortensia Chair became a real product, its iconic, textured exterior rendered in real life through 20,000 fluttering pink petals. Here, the unreal engendered the real.

This discombobulation feels appropriate, given the surreal nature of dreamscapes. These scenes do not seek to answer questions, but to propose them. The improbable interiors of Alexis Christodoulou recall the work of M.C. Escher—whose staircases you can never climb all the way up—and there is no denying the overarching reference to René Magritte, whose palette and symbolic use of architecture recur throughout this book.

But the oneiric spaces that have arisen from this genre of digital art are not always utopian. As the work of the surrealists, they can also be frightening and uncanny, designed to elicit apprehension or fear. Filip Hodas’s postapocalyptic renderings do just this: among the overgrown landscapes of his imagination stand derelict pop culture icons—lifeless Mickey Mouse heads and shattered Poké Balls. Though familiar, they are unsettling. Such scenes operate in the same way as those that are serene, working to splinter a fixed idea by introducing unreal possibilities to a scene that otherwise feels real.

Gaming, AR, VR, and special cinematic effects offer similarly strange experiences, where the laws of physics don’t apply. The designer has the power to upend gravity, to manipulate time and space. From the cyberpunk streets of Blade Runner 2049 to the Afrofuturist heart of Wakanda in Black Panther, advances in CGI are taking immersive world building to new levels.

We have never before had such capacity to render the world as we would like it to be, which means 3D modeling software has the potential to be immensely liberating. If, as it does in the dreamscapes of this book, it can free architecture and design from the constraints of reality, then surely it can do the same for other aspects of our life. Are these then visions of dreams, or of a new world entirely?

Dreamscapes & Artificial Architecture presents the imagined designs of a generation of digital artists. Available worldwide from May 5 and June 16 across America.